Hey everyone! As I mentioned in my previous posts, I’m continuing my deep dive into Computer Architecture: A quantitative approach. It’s been a fascinating journey, and today I want to chat about branch predictors – a crucial piece of the puzzle in modern processors.

But before we jump into the intricacies of branch prediction, let’s quickly recap a fundamental concept: pipelining.

Pipelining

In computer architecture, pipelining is all about efficiency. A pipeline is a technique that allows multiple instructions to overlap in execution. Think of it like an assembly line: instead of waiting for one instruction to finish completely before starting the next, we break down each instruction into stages and overlap their execution. This dramatically increases the throughput of the processor.

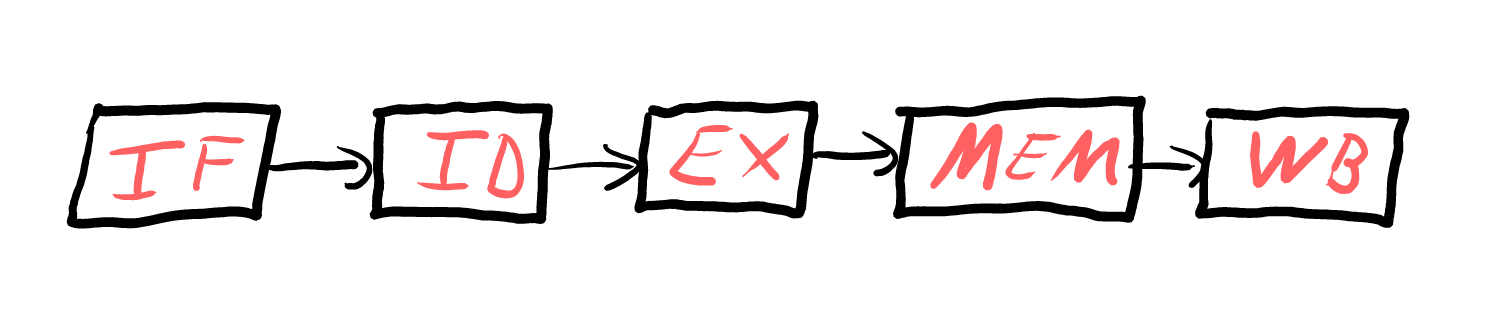

A typical instruction pipeline looks something like this:

| Typical 5 stage pipeline |

| Typical 5 stage pipeline |

Here’s a quick breakdown of each stage:

- Instruction Fetch (IF): retrieves the instruction from memory.

- Instruction Decode (ID): decodes the instruction and determines what operations need to be performed.

- Execute (EX): performs the actual operation.

- Memory Access (MEM): read or write data from/to memory.

- Write Back (WB): store the result in a register.

Branch predictors

Now, imagine you’re running a program with a bunch of conditional branches (like “if” statements). These branches can ruin our beautiful pipeline. Without branch prediction, the processor would have to pause and wait until the branch condition is evaluated, causing a pipeline stall.

That’s where branch predictors come in. They guess whether a conditional branch in the instruction flow of a program will be taken or not taken. The branch predictor’s goal is to anticipate which path the program will take before the condition is definitively known.

When a branch prediction is correct, the processor can continue executing instructions without interruption. However, if the prediction is incorrect, the processor must discard the speculatively executed instructions and fetch the correct ones, resulting in a performance penalty. Therefore, accurate branch prediction is essential for minimizing these stalls and maintaining high performance.

Different branch predictors

Of course, there’s more than one way to predict a branch. Here are a few of the most common types:

2-bit branch prediction

This predictor uses a state machine with four possible states (2²) to track the history of a branch. These states represent varying degrees of confidence in whether the branch will be taken or not taken. The states are stored in a table (often called a Branch History Table or BHT). It requires two consecutive mispredictions to change its prediction.

When a branch instruction is encountered, the predictor looks up its current state in the BHT. Based on the state, the predictor makes a prediction (taken or not taken). After the branch is executed, the actual outcome is compared to the prediction.

The state is then updated based on the actual outcome:

- If the prediction was correct, the state moves towards the “strongly” state direction.

- If the prediction was incorrect, the state moves towards the “weakly” state direction.

Correlating (or (m,n)) branch predictors

This type of predictors take branch prediction to a more sophisticated level by recognizing that the behavior of one branch can often be dependent on the behavior of previous branches. m represents the number of previous branch outcomes that are considered (the length of the global history). While n represents the number of bits used to store the prediction for each pattern (like the 2-bit counters in the 2-bit predictor).

Tournament branch predictors

Employs at least two different branch predictors, often a local predictor and a global predictor. Local predictor uses the history of individual branches to make predictions. It maintains a separate history for each branch. Global predictor uses the history of recently executed branches to make predictions. It captures correlations between different branches. A selector is used to choose which of the predictors should be used to make the final prediction for a given branch. They offer high accuracy by adapting to different branch patterns.

Tagged hybrid predictors

Tagged hybrid branch predictors represent a sophisticated evolution in branch prediction, aiming to combine the strengths of different prediction mechanisms while mitigating their weaknesses. Like tournament predictors, tagged hybrid predictors combine multiple prediction mechanisms. However, they go a step further by using tags to select which predictor’s prediction to use.

Tags are used to associate specific prediction patterns with particular branch instructions or instruction sequences. These tags help the predictor dynamically choose the most appropriate prediction mechanism for each branch. The selection of the predictor is not a static choice, but rather a dynamic one that adapts to the runtime behavior of the program. This allows the predictor to adjust to changes in branch behavior.

The Branch-Target Buffer (BTB)

Branch predictors often work hand-in-hand with a special cache called the Branch-Target Buffer (BTB). The BTB stores the target addresses of recently executed branches, allowing the processor to quickly jump to the correct location without recalculating the address.

Choosing the right predictor

So, which predictor is the best? It really depends on the trade-off between accuracy and hardware cost. Generally, accuracy increases as we move from 2-bit predictors to tagged hybrid predictors, but so does complexity and cost.

In the end, the choice of branch predictor is a careful balance between performance and practicality.

I hope this gives you a better understanding of branch predictors and their role in keeping modern processors running smoothly. As always, I’m continuing my journey through computer architecture, and I’ll be sharing more insights as I go. Stay tuned!